A hardy yeast infection has researchers in Canada and around the world worried about the rise of a new generation of drug resistant superbugs.

There are fewer than 20 documented cases in Canada so far but the fungus known as Candida auris has epidemiologists and public health officials concerned.

“The reason that we’re concerned about it is because these organisms seem to be able to transmit between patients very efficiently within hospitals and because they have intrinsic resistance to the antifungal medication that we would typically use for a patient that has an invasive yeast infection,” said Dr. Ilan Schwartz, an infectious disease physician and assistant professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

“The rapid spread of this organism is quite alarming but what’s most alarming is the difficulty that we have in eradicating it from hospitals once it has arrived, and in treating patients that are infected.”

(click to listen to the full interview about Candida auris with Dr. Ilan Schwartz)

In fact, eradicating the fungus from hospitals is so difficult that last year the Brooklyn branch of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York State had to bring in special cleaning equipment and rip out some of the ceiling and floor tiles to eradicate it.

Candida auris is a yeast fungus that was first described in 2009, when it was isolated from the ear canal of a patient in Japan – hence its name auris, which means ear in Latin, said Schwartz.

“However, the clinical significance of it has since become much more clear and it’s much more fearsome than just something causing ear infections,” said Schwartz, who has been studying the superbug.

Global reach

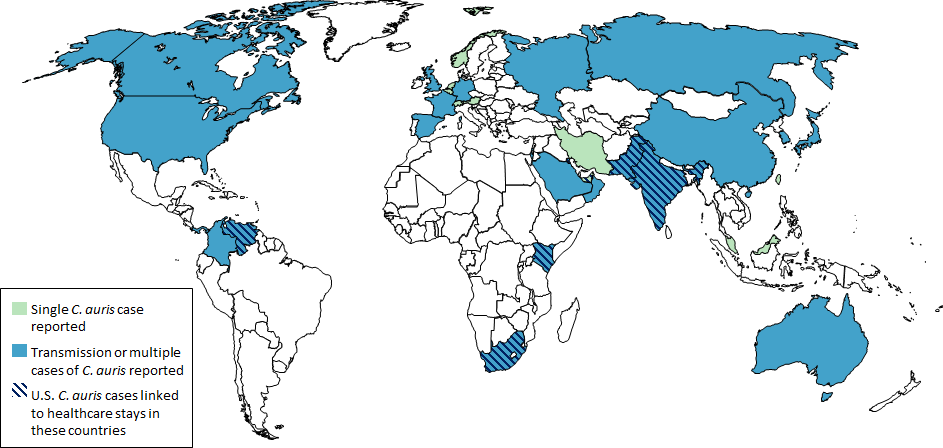

(Source: CDC)

Over the ensuing decade, Candida auris (C. auris) has spread to 32 countries, including Canada, which reported 19 cases from 2012 to February 2019, according to Health Canada statistics.

There were 6 cases in Central Canada (Quebec and Ontario) between 2012 and 2017, and 13 cases in Western Canada (Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia) between 2014 and February 2019.

C. auris is a relatively new bug and it was traced back to 2006 when scientists with the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) analysed samples of yeast isolates.

“For some reason it really wasn’t around before then,” Schwartz said. “But at the same time scientists at the CDC and elsewhere have analysed the isolates that have been found and determined that they come from at least four different geographic regions and the all seemed to have emerged independently but simultaneously, which is very odd.”

High mortality rate

C. auris usually infects people who are already quite sick, Schwartz said.

“Generally these are patients that are admitted to intensive care units for other reasons, often it’s because of pre-existing problems like cancer or sometimes surgery,” Schwartz said. “These are patients that generally have been in hospital for a long time and end up in the intensive care unit.”

Usually, these patients have already been exposed to a lot of antibiotics and have catheters and intravenous tubes going into their veins, he said.

“Generally these patients do very poorly: the mortality rate is about 30 to 40 per cent for patients for whom the yeast is in the blood stream,” Schwartz said.

The germ is usually contaminated from the skin of patients who become colonized and then transmit it to the environment – the hospital room, various appliances and tools that are used for monitoring and caring for patients, he said.

“Now, there is a process for decontamination of any tools that touch one patient and are going to touch another but because of the particularly hardy nature of Candida auris we have seen outbreaks around the world where these protocols aren’t adhered to very closely,” said Schwartz.

Efforts to control the spread

The National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and a group of doctors and public health officials from hospitals across Canada have been working together to monitor the spread of C. auris, he said.

There is also a network of provincial laboratories that are able to identify drug resistant organisms and could refer these samples to the National Microbiology Laboratory, Schwartz said.

“The Public Health Agency of Canada’s (PHAC) National Microbiology Laboratory began surveillance of C. auris in January 2018 after Canada’s first case of multidrug resistant C. auris was detected in a returning traveller,” said Anna Maddison, a spokesperson for Health Canada and PHAC.

In January 2019, PHAC’s Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program initiated ongoing surveillance of C. auris among hospitalized patients, she added.

“PHAC is reviewing existing evidence and available guidance to update our infection prevention and control guidance document for C. auris,” Maddison said. “Canada’s public health laboratory network is well-equipped, working in collaboration with health-care facilities, to detect and address C. auris.”