Three Indigenous groups from British Columbia will get a greater say in talks between Ottawa and Washington to modernize a bilateral treaty that coordinates flood control and hydropower generation along the Columbia River, Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland announced Friday.

Representatives of three Indigenous Nations whose traditional territory encompasses the Upper Columbia Basin in B.C. – the Ktunaxa Nation, Secwepemc Nation and Sylix Okanagan Nation – will now participate as official observers in the negotiations, Freeland said.

“I am delighted that, for the first time, Indigenous Nations will officially join our negotiations with the United States about the future of the Columbia River Treaty,” Freeland said in a statement, thanking the First Nations for their patience.

“By working together, we will ensure that negotiations directly reflect the priorities of the Ktunaxa, Okanagan, and Secwepemc Nations – the people whose livelihoods depend on the Columbia River and who have resided on its banks for generations.”

Change of discourse

Friday’s announcement, which came following Freeland’s April 24 meeting with the leadership of the three nations and Katrine Conroy, B.C.’s minister responsible for the Columbia River Treaty, in Castlegar, marked a significant change of tone between the Indigenous groups and the federal government.

When the negotiations began in May of 2018, the three Indigenous groups accused Ottawa of excluding them from direct participation in the talks, calling it “blatantly inconsistent” with the Liberal government’s stated goal to advance reconciliation with Indigenous Canadians.

“The original Columbia River Treaty in 1964 excluded our Nations, and wreaked decades of havoc on our communities and the basin,” said in a statement Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, chair of the Okanagan Nation Alliance.

“Canada’s unprecedented decision to include us directly in the U.S.-Canada CRT negotiations is courageous but overdue and necessary to overcome the decades of denial and disregard.”

However, U.S. authorities have no plans to follow in Canada’s footsteps.

“It is our foreign policy judgement that the best way to balance the United States’ objectives and conclude a successful agreement with Canada in a timely manner is to limit the negotiating team to federal agencies,” a spokesperson for the U.S. State Department told Radio Canada International.

U.S. officials have maintained regular contact and communication with tribal officials and their input has been incorporated in the American negotiation position, the State Department official said in an email.

“We will continue to engage the Tribes on a regular basis as negotiations proceed,” the State Department official said.

Giant water management project

FILE – This June 3, 2011, file photo shows the Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River near Cascade Locks, Ore. Talks are scheduled to continue on June 19 and 20, 2019, in Washington, D.C., to modernize the document that coordinates flood control and hydropower generation in the U.S. and Canada along the Columbia River. (Rick Bowmer/AP Photo/File)

The Columbia River Treaty (CRT) is the largest international water storage agreement between Canada and the U.S.

The treaty sets a protocol for managing how much water Canada will release annually from the river’s headwaters and how much the U.S. will pay in return.

The U.S. and Canada began taming the mighty river system in the 1930s with construction of a series of more than 450 dams along the Columbia basin, which drains a watershed the size of France across seven U.S. states and B.C.

While the project was praised for generating electricity for the area and irrigating farmland, Indigenous groups in Canada and the U.S. mourned the loss of traditional salmon fishing grounds but hoped negotiations to modernize the treaty governing the river could resolve this.

Major impacts on Indigenous communities

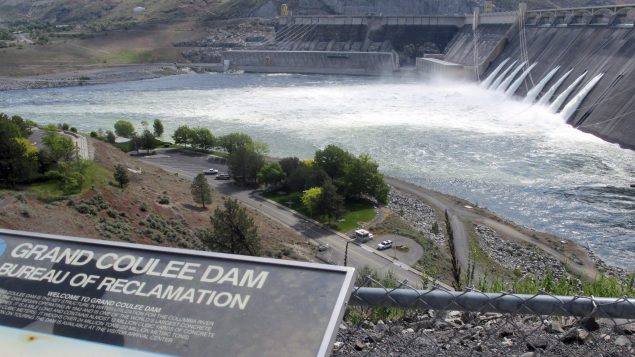

FILE – In this June 1, 2011 file photo, water is released through the outlet tubes at Grand Coulee Dam, Washington (Nicholas K. Geranios/AP Photo/File)

Jay Johnson, one of the negotiators on behalf of the chief’s executive council of the Okanagan Nation Alliance, said the impact of the treaty on Indigenous communities in Canada has been “pretty dramatic.”

“There has been the loss of hundreds of thousands of species from inundation and flooding of valley bottoms in the Kootenays,” Johnson said. “There is the loss of burial sites and village sites under water, there is sacred sites that are no longer accessible because they’re under water.”

The operation of the treaty has focused on accommodating power generation, mostly in the U.S., he said.

“That means that you’re basically holding back the spring runoff every year and releasing it over the fall and early winter, and then drawing down the basin so it fills back up in the spring,” Johnson said. “You have a fluctuating water system that can quite easily fluctuate up to 80 feet (24.3 metres) any given year, which is beyond anything in the normal natural cycle.”

Indigenous groups on both sides of the border hope the revised agreement will prioritize fishing by adding a third pillar alongside hydropower and flood control, the so-called “ecosystem-based function”.

Rebuilding natural salmon habitat

The United States and Canada held the sixth round of negotiations to modernize the Columbia River Treaty regime on Apr. 10 and 11 in Victoria, B.C. U.S. and Canadian negotiators discussed issues related to flood risk management, hydropower, and ecosystem benefit improvement, according to a press release by the State Department.

“We see the Columbia River Treaty as really only having two legs of the stool as it’s often referred to: it is for flood control and probably more importantly power generation,” Johnson said. “And, obviously, the other leg of the stool is ensuring that there is an ecosystem function deeply embedded in the system.”

Ensuring that Indigenous voices both in Canada and the U.S. are included in the governance of the whole process, would add a fourth leg to that proverbial stool, making it much more stable, Johnson said.

Canadian Indigenous groups would like to replicate the success in rebuilding the sockeye salmon population in the Okanagan river system, which is a tributary to Columbia River in the wider Columbia River Basin, he added.

The next round of negotiations is scheduled to take place in Washington, D.C., from June 19 to 20.

With files from Reuters